By Jeanne-Marie Jackson, Johns Hopkins University

African literature is the object of immense international interest across both academic and popular registers. Far from the field’s earlier, post-colonial association with marginality, a handful of star “Afropolitan” names are at the forefront of global trade publishing.

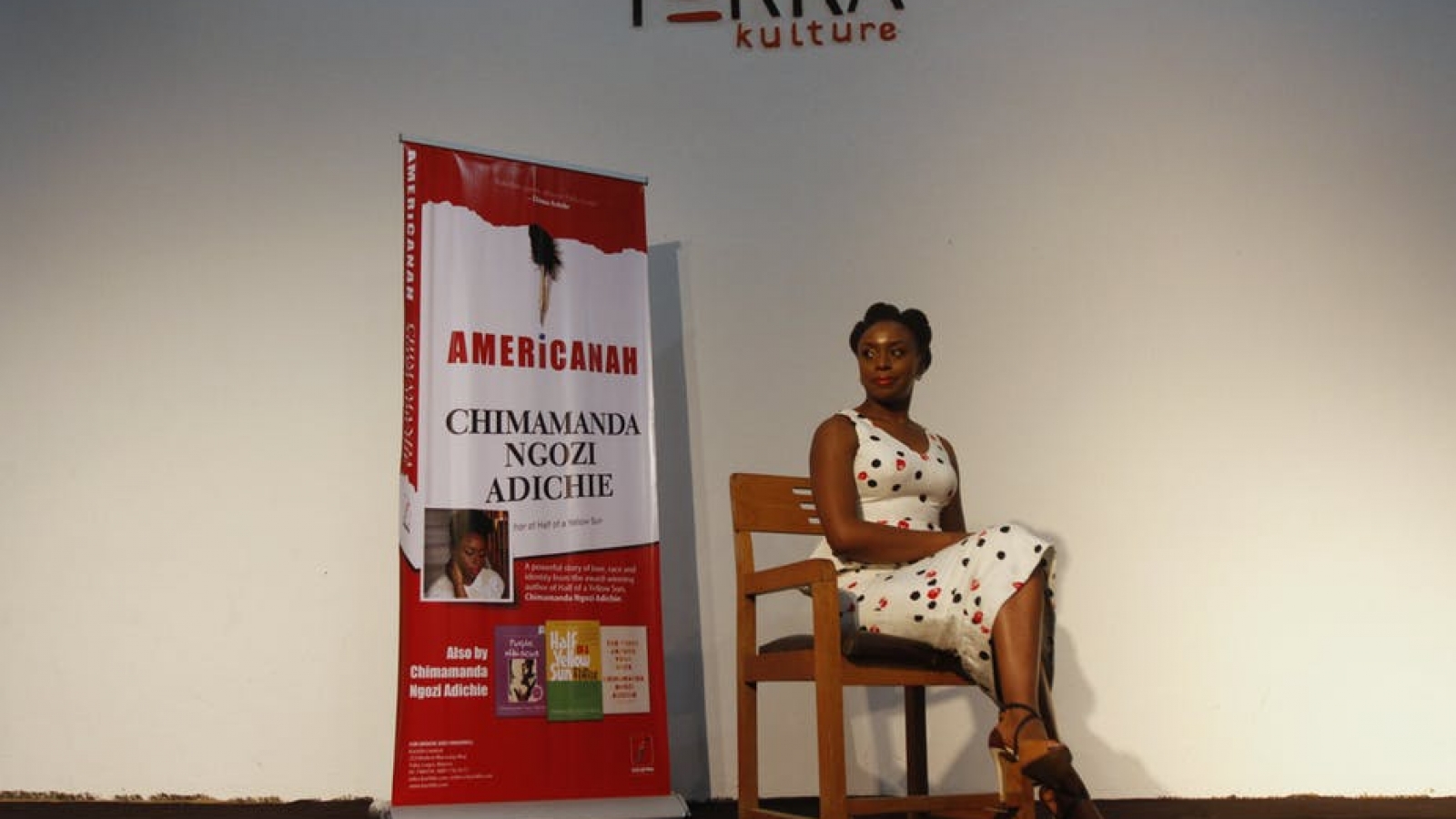

Books like Chimamanda Adichie’s “Americanah” and “Half of a Yellow Sun”, Teju Cole’s “Open City”, Taiye Selasi’s “Ghana Must Go” and Yaa Gyasi’s “Homegoing” have confounded neat divisions between Western and African literary traditions. The Cameroonian novelist Imbolo Mbue captured a million-dollar contract for her first book, “Behold the Dreamers”. That’s even before it joined the Oprah’s Book Club pantheon this year.

Such commercial prominence, though, has attracted considerable and unsurprising push back from Western and Africa-based critics alike. Far from advancing narratives with deep roots in local African realities, such critics fear, many of Africa’s most “successful” writers hawk a superficial, overly diasporic, or even Western-focused vision of the continent.

The most visible of these critiques has been directed at the Zimbabwean writer NoViolet Bulawayo’s “We Need New Names” (2013). The Nigerian novelist Helon Habila worried in a review in the London Guardian that it was “poverty-porn”. The popular Nigerian critic Ikhide Ikheloa (“Pa Ikhide”) frequently makes a similar point. Fellow Nigerian writer Adaobi Nwaubani critiqued the West’s hold on Africa’s book industry in a much-circulated New York Times piece called “African Books for Western Eyes”. Continue Reading